One leaked password to a critical account is a tragedy; 1.3 billion may just seem like a statistic. But security expert Troy Hunt's herculean task of combing through a massive roster of stolen logins provides some very practical insights for all of us.

What matters is not so much the magnitude of passwords captured by crooks and sold to other crooks trying to break into accounts. This is the biggest list Hunt has analyzed, but it aggregates multiple leaks that have already happened. More important is what Hunt's conversations with a handful of individuals reveal about how people use and reuse these passwords, sometimes over decades.

Hunt's blog post about the investigation contains powerful anecdotes from some of the 5.9 million people who subscribe to his free security breach monitoring service, Have I Been Pwned. (This includes 2.9 million whose data has been leaked.) One subscriber said that they were no longer using a six-character password on the list but were still using another, eight-character item. As Hunt reports, "#2 referred to above was just #1 with two exclamation marks at the end!!".

Even with just that first, six-character password, hackers probably would have arrived at the second one pretty quickly. They use automated tools that generate oodles of new passwords to try on sites. Hunt gives a real-world example of another password, "Fido123!", which has already been exposed to hackers. It's a bad password, writes Hunt, "because it's named after your dog followed by a very predictable pattern." Hunt doesn't speculate more on this particular example, but I wonder how many "Rover123!", "Kitty123!", "Mommy123!", etc., are out there.

That's dangerous because many of the passwords were also paired with email addresses, and some addresses were paired with multiple passwords. (A few are nonsensical, though, such as the pairing of one of Hunt's own emails with an IP address, rather than a password.) Hunt doesn't reveal the exact number of pairings, in part because he stores passwords and emails separately so as not to create another target for hackers. But even just an email is vulnerable if the owner's logins used passwords that are easily guessable (using powerful hacking software).

And how often are those passwords reused – allowing one leaked login to unlock multiple accounts? Another subscriber whose password was in the breached list told Hunt, "Yes that was a password I used for many years for what I would call throw-away or unimportant accounts between 20 and 10 years ago." Do even unimportant accounts still have sensitive information, even 10 years later? Possibly. And might that password also have slipped into an "important" account login?

How to Find and Kill Bad Passwords

Luckily, it's pretty easy to root out your lousy logins, if they are stored in a password manager. And they may be, even if you don't realize it. If you don't have to enter your username and password every time you log into a site, it's probably because they have been automatically stored in your web browser or operating system. (Google Chrome, for instance, incorporates the Google Password Manager.) Those are as much password managers as the third-party apps such as 1Password, Bitwarden, or Dashlane that security purists set up.

Many also have tools to check your stored logins against databases of known leaked email addresses, such as Hunt's Have I Been Pwned. Subscription-based 1Password connects to Hunt's databases for a feature called Watchtower, which he recommends. (Hunt does disclose that he has a business partnership with the company.) Watchtower has other features, such as identifying weak passwords and passwords you have reused.

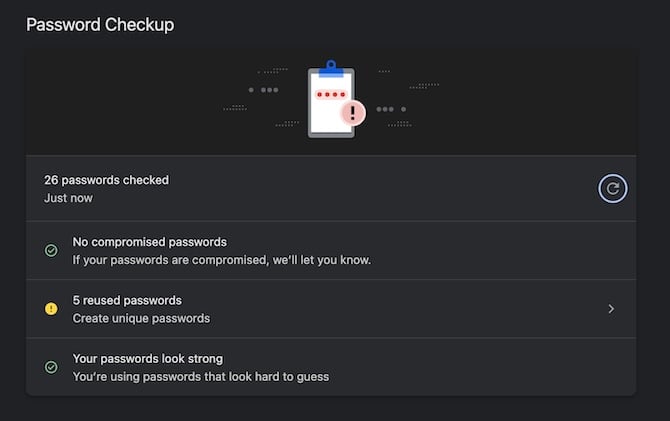

There are also similar free tools built into web browsers. Google's Chrome on desktop, for instance, click the three dots in the upper right of the window and go to Settings > Privacy and security > Safety Check. In Microsoft Edge, click the three dots and go to Passwords > Password security check. In Safari on macOS, go to Settings > Passwords > Open Passwords > Security. These steps may vary a bit depending on your software version.

Read more: Everything You Need to Get Started with Google Password Manager

Begin your efforts with the most important sites, such as Google, Apple, your financial institution, e-commerce sites that store your payment information, and any health or government benefits accounts. Absolutely change any passwords that have been leaked or duplicated on other sites. Also, to beef up ones that are weak: few characters with those predictable patterns a la "Fido123!".

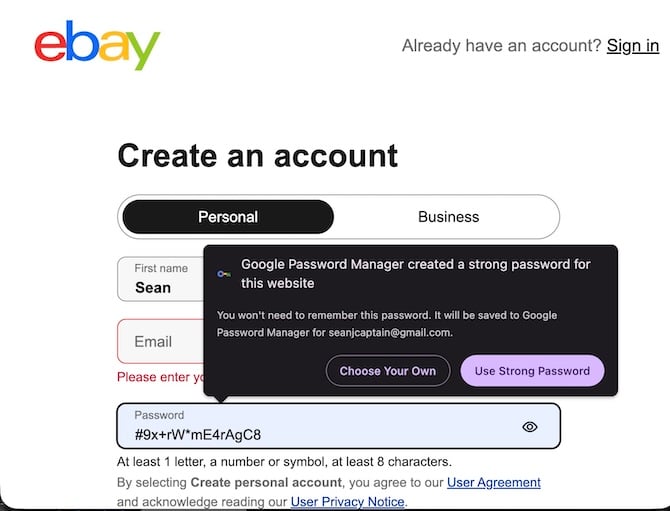

Once again, your password manager can help. It will offer to create a strong password (such as "cFW2HKpshj.aWn", which Chrome just made for me) for you or save any one you want to enter. The best way to go is what’s called a passphrase – a nonsensical expression such as "Unclip-Parlor3-Doze". They’re very long and therefore very hard for hackers to guess. But they are easier to type in than something like "cFW2HKpshj.aWn". (Browsers don't tend to generate passphrases for you; but third-party apps do, including the free version of Bitwarden.)

Now you can also go one step farther, replacing passwords with a login method called passkeys. The tech uses encryption technology to generate two related values, called keys – one residing with a website or app, the other in your password manager. (See our passkeys explainer to learn more.) Passkeys are gradually rolling out across the biggest sites on the Internet, including those sensitive sites like Amazon, eBay, Google, Microsoft, Target, Walmart, and Wells Fargo.

For all the other sites that don't yet support passkeys, there is two-factor authentication. Yes, it's tedious to copy-paste or type in those 2FA codes you get via text message. But this process vastly reduces the chance of someone getting into your account – even if you have a leaked email address and a pathetically poor password (which is still not an excuse for poor passwords).

You don't have to lose a whole weekend doing all this work at once. Start with spiffing up the passwords (or better yet, replacing them with passphrases) on your major accounts, and set up two-factor authentication if you haven't already. You can gradually work your way through the list of sites. As for passkeys, many sites will nudge you to set one up and guide you through the process. (It's just a few clicks.) So you can do that as the opportunities arise.

[Image credit: Sean Captain/Techlicious via ChatGPT]